How to Solve Insider Trading in Prediction Markets

How platform guardrails, market design, and regulation can address the problem of insider trading in prediction markets.

When the man across the table knows how the game ends, your only move is to fold.

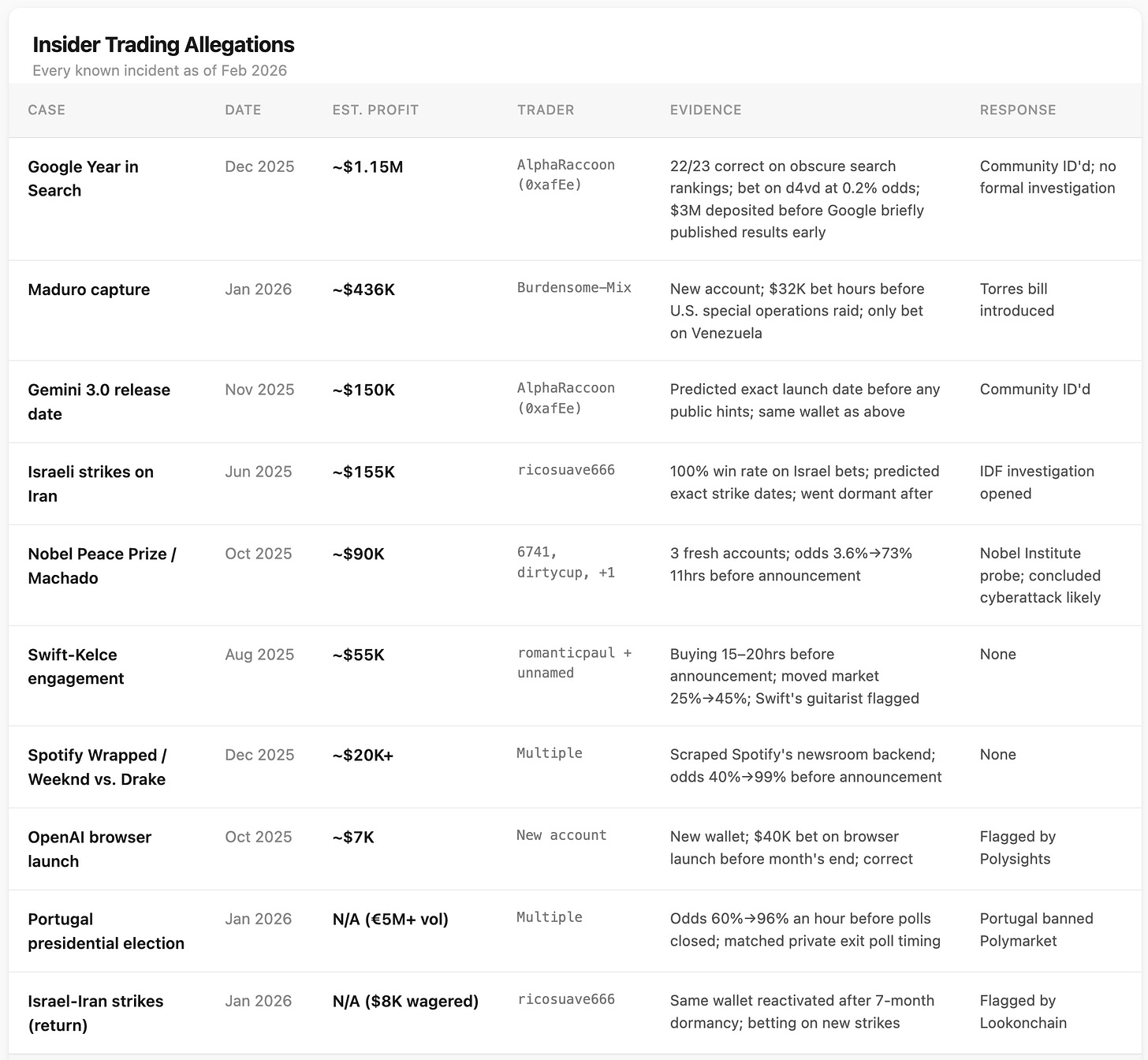

In late 2025, a pseudonymous trader on Polymarket that went by AlphaRaccoon began placing bets on one of the most obscure corners in prediction markets: Google’s Year in Search trends. Every December, Google publishes a ranking of the year’s top trending search topics, a proprietary data set known in advance only to a small number of employees inside the company. On Polymarket, you could wager on which topics would make the list and how they’d rank. Most traders treated these contracts as low-stakes entertainment. AlphaRaccoon predicted 22 out of 23 search rankings correctly and made over a million dollars. Months earlier, the same wallet made over $150,000 by predicting the exact release date of Google’s Gemini 3.0.

This isn’t an isolated incident. There are allegations of insider trading in several markets: Taylor Swift’s engagement proposal, the 2025 Nobel Peace Prize winner, the US intervention in Venezuela, the release date for OpenAI’s GPT 5.2 model, and the results of over 100 UFC fights.

Now, athletes and their associates, musicians and their friends, founders and employees of technology companies, and politicians and their staff, all have privileged access to information they can trade on. When nearly everything becomes a market, nearly everyone has inside information.

The democratization of investing leads to the democratization of white collar crime.

The Debate

“Insiders make prices more accurate”

There is a real intellectual argument that insider trading on prediction markets is actually desirable. Robin Hanson, the economist often called the “godfather of prediction markets,” is the biggest proponent. The point of prediction markets is to produce accurate prices, and insiders have the most accurate information. Banning them from trading is like banning your best sources from contributing to a newspaper.

Insider trading is banned for stocks because stocks exist to raise capital. If insiders could trade on private information before it’s public, they’d extract value from new investors buying shares, making those investors unwilling to buy at fair prices and forcing companies to raise capital at a much higher cost. But prediction markets exist to surface truth.

When AlphaRaccoon bought Google Year in Search contracts, the prices moved, and anyone watching could have inferred that someone with inside knowledge believed specific outcomes were near-certain. The insider’s trade was itself a signal, and the market was doing exactly what it was designed to do.

The argument has holes. If insiders dominate a prediction market, market makers (who take the other side of the trade) bleed, and without their liquidity, the market becomes thinner, more volatile, and paradoxically less informative. Second, there’s the problem of incentive corruption: if a tech executive can bet on their own product launch date and then adjust the schedule, or a government official can wager on geopolitical outcomes they have the power to influence, the market hasn’t surfaced “the truth.” It has created a financial incentive for manipulation.

Third, and most importantly, insider trading will not survive scale: if prediction markets grow 10x in volume, the public will not tolerate insiders making millions of dollars trading on privileged information. It is inevitable for regulators to step in to preserve market integrity.

The history of stock market regulation tells a similar story. When ordinary investors conclude the game is rigged, they stop playing. Trading volume on the NYSE fell 90% between the 1929 crash and 1932. It took the Pecora Commission hearings that exposed systemic fraud and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, which specifically banned insider trading, to restore enough confidence for markets to function again.

The most defensible case for insider trading, however, is where the public value of the information is enormous and there’s no other reliable channel to surface it. A researcher at the Wuhan lab in December 2019 had no institutional incentive to raise the alarm about coronavirus cases, and the institutions that should have, like the Chinese government, actively suppressed it. If that person could have made $100,000 betting on a pandemic contract, the price signal would have been visible to epidemiologists, journalists, and governments weeks before the official acknowledgment. The profit motive becomes a whistleblowing mechanism.

The problem is that these cases are rare, and the framework you’d build to encourage them also enables all the harmful ones (Gemini release dates, UFC fights, Taylor Swift’s engagement). You can’t write a rule that says “insider trading is fine when the information is important to humanity”. But it’s fair to say that some permissionless markets will always exist, and that helps surface information that may be suppressed.

“Prediction markets aren’t stocks, so stock market rules don’t apply”

The second argument for insider trading is a legal one. Prediction market contracts are commodity derivatives regulated by the CFTC, not securities regulated by the SEC. Derivatives markets are designed to let informed participants trade on proprietary information. A corn farmer trading futures based on private knowledge of his own crop isn’t committing fraud; he’s doing what the market was built for. The CFTC’s standard asks whether information was stolen, not whether trading on it was unfair. Extending SEC-style insider trading doctrine to prediction markets, in this view, means importing a framework from a market with a fundamentally different economic purpose.

But derivatives markets tolerate informed trading because the underlying product (corn, oil, interest rates) is continuous, with prices shaped by many competing participants over time. Even when dominant players exist (OPEC can move oil prices with a single production decision), these markets have deep independent liquidity and decades of regulatory infrastructure built to manage exactly that risk.

Prediction market event contracts have none of this. The “commodity” is a binary question with a single definitive answer, often known in advance by a tiny number of people. When a Google employee bets on Year in Search rankings, there is no crowd of competing informed participants and no regulatory scaffolding. Few people know the answer and everyone else is guessing. The legal distinction between derivatives and equities is real, but it’s an argument for writing new rules tailored to prediction markets, not for concluding that no rules are needed.

How to Solve Insider Trading

There are three broad approaches to address insider trading in prediction markets: platform guardrails, market design, and legal frameworks.

Platform Guardrails

The most direct interventions are at the platform level: detection, identity verification, and trade controls.

Detection. Kalshi announced that they run a proprietary system called “Poirot” that uses pattern recognition to flag suspicious trades in real time. In the past year, they reported over 200 investigations and multiple account freezes. They recently expanded this through a partnership with Solidus Labs, whose “HALO” platform layers behavioral analysis on top of order flow data. On the unregulated side, an ecosystem of third-party tools has emerged: Tre Upshaw’s Insider Finder (roughly 24,000 users, funded in part by a $25,000 Polymarket grant) scans the blockchain for anomalous trades and reports an 85% success rate on flagged situations turning profitable. Similar tools like Unusual Predictions and PolyInsider do the same: they make suspected insider trading as a signal to copy.

Progressive KYC. Identity verification requirements could scale with position size, letting casual bettors trade pseudonymously while forcing large, suspicious positions (like ricosuave666’s four simultaneous bets on Israeli airstrikes from a brand-new account) through meaningful identity checks. Kalshi already requires full KYC for all users. The challenge is implementing this on crypto-native platforms without killing permissionless onboarding.

Position limits and trade disclosure. A $5,000 cap for wallets less than 30 days old would have made most insider trades more difficult. Mandatory trade disclosure with delays, modeled on the SEC’s Form 4 for corporate insiders, would give the public systematic data on large positions rather than forcing community tools to scrape the blockchain ad hoc. A trader could still generate new wallets and rotate IP addresses through a VPN. But more sophisticated surveillance tools can identify wallet clusters, especially when they’re funded from the same centralized exchange withdrawal. These systems don’t make insider trading impossible; they just make it harder to get away with.

Automated public alerts. If a large, suspicious-looking trade is placed in a market, the platform notifies all participants immediately. This converts the information asymmetry that makes insider trading profitable into the public signal that Hanson’s defenders claim it is. Building this into platform infrastructure would make it systematic and harder to game.

Market Design

A prediction market needs someone willing to take the other side of a trade, and that counterparty systematically loses money to insiders. The question is how to design the plumbing so those losses don’t drive everyone else away.

The status quo. Robin Hanson’s Logarithmic Market Scoring Rule (LMSR) is an automated market maker that provides continuous quotes with a bounded maximum loss. When an insider trades against it, the LMSR absorbs the loss and adjusts the price. That loss is the cost of price discovery: the platform subsidizing accurate prices the way a newspaper pays reporters. This works for smaller markets (corporate forecasting, research) but can’t support the billion-dollar volumes Polymarket and Kalshi now process. Polymarket moved to a Central Limit Order Book (CLOB), which shifts insider losses from an algorithm to human market makers. Those market makers eventually respond by widening spreads or leaving, producing the same adverse selection spiral.

Dynamic spread widening. Platforms could automatically widen the bid-ask spread in a specific market when surveillance detects suspicious activity, making it more expensive for insiders to trade. This is what traditional market makers do intuitively when they suspect informed flow. Automating it would protect liquidity providers in real time.

Market maker insurance pools. A pool funded by trading fees could partially reimburse market makers for verified insider trading losses after a market resolves. This wouldn’t prevent insider trading, but it would keep market makers in the game.

Segmented order flow. Market makers could offer tighter spreads to verified accounts and wider spreads to unverified ones, creating a two-tier system where insiders effectively pay more for execution. This is feasible on platforms like Kalshi and Polymarket, where order matching happens off-chain. It’s harder for fully onchain order books.

Time-weighted settlement. Contracts could resolve based on a price-path average (similar to a Time Weighted Average Price) rather than a single binary moment, making it harder for insiders to profit from a single perfectly timed trade. This works better for some contract types (product launches, earnings) than others (military operations, sudden events).

None of these eliminates insider trading, but together they keep liquidity providers in the game, which preserves the broad participation that makes prediction markets useful.

Legal Framework

The legal solutions are ordered from what can be implemented today to what requires an act of Congress.

Corporate compliance. The private sector is moving faster than Congress. KPMG’s 2025 report flagged prediction market insider trading as an emerging corporate risk. Most insider trading policies don’t contemplate employees betting on their employer’s decisions via event contracts. Compliance experts have urged large companies to update their policies to add event contracts to restricted trading lists.

Existing CFTC authority. The CFTC has anti-fraud authority under Section 6(c)(1) of the Commodity Exchange Act and Regulation 180.1, which prohibit trading on material nonpublic information obtained through fraud or deception, or in breach of a pre-existing duty, such as an employee’s obligation to their employer or a contractor bound by a confidentiality agreement. But this is narrower than the SEC’s Rule 10b-5, because it requires not just possession of inside information but a link to deception or duty, a higher bar for prosecution. The CFTC has never brought an insider trading case targeting prediction market event contracts, and the agency has roughly one-eighth the staff of the SEC. Its most important near-term move would be issuing guidance clarifying how its existing authority applies to prediction markets: what counts as material nonpublic information for event contracts, and what “pre-existing duty” means in this context. This wouldn’t require new legislation; the agency would use the authority it already has.

New legislation. Representative Ritchie Torres proposed the “Public Integrity in Financial Prediction Markets Act” (H.R. 7004), which would ban federal government employees from trading on contracts where they possess material nonpublic information through their official duties. But the bill is narrowly scoped: it covers government employees and says nothing about corporate insiders, deliberative bodies like the Nobel Committee, or sports and entertainment. The cleanest path is an amendment to the Commodity Exchange Act that explicitly defines insider trading on event contracts and gives the CFTC enforcement authority comparable to what the SEC has under Rule 10b-5, establishing that anyone with privileged access to the outcome of an event contract owes a duty not to trade on that information. But legislation carries its own risk. Compliance regimes modeled on securities law could impose costs that only well-funded incumbents can absorb, giving incumbents a regulatory moat. The goal is to define what counts as insider trading on event contracts, not to build a licensing apparatus that kills prediction market upstarts before they launch.

Conclusion

Every major financial market has gone through a similar cycle: a period of explosive, lightly regulated growth; a series of scandals that reveal the cost of operating without rules; a political fight over what the rules should be; and then, after the rules are established, a longer and more durable period of growth built on broader participation and institutional trust.

The New York Stock Exchange operated for over a century before the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 created the SEC. For decades, insiders traded freely on advance knowledge of earnings, mergers, and corporate decisions. It took a stock market crash, a Congressional investigation, and a 90% collapse in trading volume to create the political will for federal oversight. But once the rules were in place, capital markets grew.

Prediction markets are somewhere in the early chapters of that same story. The AlphaRaccoons and ricosuave666s are this era’s pool operators, the traders in the 1920s who exploited unregulated markets until public outrage led to rules. Prediction markets will likely mature the way equity markets did: platforms build out detection, corporate compliance departments add event contracts to their restricted lists, regulators issue guidance and bring enforcement actions, the CFTC or Congress extends the insider trading doctrine to event contracts, and international regulators follow suit.

super informative read

The Robin Hanson reasoning--that insider trading is the point--seems hard to overcome. Banning insider trading on prediction markets would seem to reduce their ability to create information.

With that said, I myself no longer will be a participant in any markets in which I don't have insider information. There is too much adverse selection in a market where trading on insider info is allowed.

I think you should write a post about the emerging derivatives on prediction markets. (https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/LBC2TnHK8cZAimdWF/will-jesus-christ-return-in-an-election-year https://derivative.polymarket.com/jesus-christ-return-before-2027-odds-5-february-17-12-1-am-3)