Financial Speculation in Ancient Rome

Today, people believe the path to escape the permanent underclass is not through hard work but by financial speculation. Ancient Romans thought the same.

The average zoomer and millennial believes that a traditional job is a road to the permanent underclass.

Housing is out of reach: homes cost 7 times median income today

Student debt lingers on for decades: the average student takes 20 years to pay off their debt

Healthcare costs have exploded: insurance premiums have quadrupled since 2000

People believe that the primary way to escape the permanent underclass is not through hard work or expertise but financial speculation. Hundreds of millions of people are trading meme stocks and crypto currencies, betting on sports games, gambling in online casinos, and buying lottery tickets.

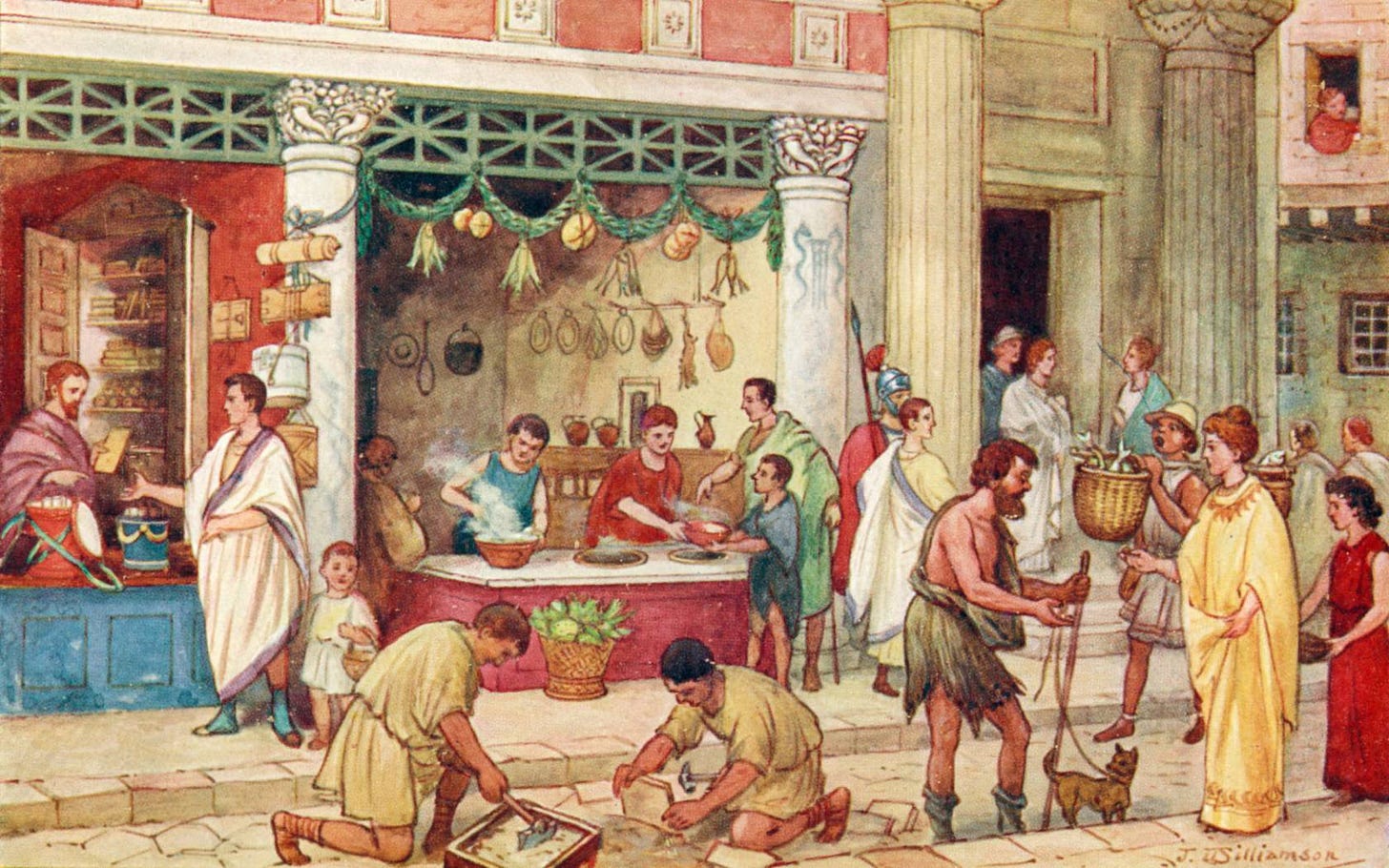

This feels unprecedented, and the scale certainly is, but are there any historical analogues to this sentiment? Interestingly, yes. One of the earliest examples comes from Ancient Rome.

In Daily Life in Ancient Rome, historian Jerome Carcopino writes, “Work might still ensure a modest living, but no longer yielded such fortunes as imperial favor or a speculative gamble might bestow… speculation was the life-blood of an economic system where production was losing ground day by day.”

He is describing Imperial Rome at its height in the 2nd century AD, where big fortunes came from speculation and favorable access to the emperor, not craftsmanship and production.

At the late stages of many empires, speculative activity increases.

Complex Markets: Necessary Condition for Financial Speculation

By the 2nd century BC, Rome had developed complex markets: property transfers, loans with interest, exchange of foreign currency, the use of bankers’ draft, and a primitive form of insurance for ships and other property.1 Complex markets are a necessary condition for financial speculation.

In Latin, speculator describes a sentry whose job it is to “look out” for trouble. Speculators met at the Forum where they bought and sold shares, bonds, goods, farms, houses, ships, cattle, and slaves. The Roman comic playwright Plautus describes two types of men at the Forum: those who would boast (bulls) and those who would spread accusations about one another (bears).

Speculating on the State

Rome often hired the publicani (state contractors), which were effectively private companies, to perform essential state functions like collecting taxes, buying grain, and building temples for the city. Like joint stock companies, the publicani had independent members who owned shares in them, which included capitalists, politicians, and merchants.

Through shares in the publicani, common people had a financial interest in the construction and repair of public buildings, and revenues from navigable rivers, harbors, gardens, mines, and lands. Privileged knowledge of state decisions, for example about when the state would buy grain or where it would construct a temple, fueled speculation and made some people rich overnight.

Speculating on Grain

A typical deal between the state and the publicani (contractors) worked like this: the contractor paid a fixed fee to win the job, sent agents into the countryside to collect grain at a low price, then sold that grain at a profit into the city’s food program.

Speculative gains were made when the state bought grain at higher prices or higher volumes during shortages.2 This created a strong financial interest in shortages, emergencies, war, and famine. Contractors actively hoarded grain supplies only to release them during severe shortages. They would get privileged information of when and where shortages might exist from state officials. Many senators were themselves involved in the grain trade so had a financial interest in exaggerating shortages.3

One season of contracts could move millions of sesterces, the everyday Roman coin; for comparison, a regular soldier earned about 900 sesterces in a year.4

It was more profitable to speculate on grain prices and hoard grains for months than to work as a carpenter, mason, or blacksmith at the height of Imperial Rome. A carpenter or mason’s income rose only with the hours he worked, but a grain speculator who timed one winter correctly could capture a season’s worth of profit in a few days.

Gambling and Dice

Gambling was part of everyday life in Rome, and most adult men played semi-regularly. People rolled cube dice and tossed knucklebones at their homes and in taverns; emperors played too, which made it feel normal. Tables used simple rules: a bad throw cost a coin, the best throw took the pot. Julius Caesar famously said, “the die is cast” when he crossed the Rubicon in 49 BC; he was comparing his decision to a dice throw: once the dice leaves your hand, you can’t take it back. Clearly gambling on dice was something everyone could relate to.

Stakes were usually small: four sesterces, about 5% of a soldier’s monthly salary. There were flashier gamblers like Roman emperor Claudius who reportedly bet 400,000 sesterces on a single roll of dice, and even wrote a treatise on the art of dice that is now lost.

Roman law mostly banned gambling outside festival windows and threatened fines and infamia (loss of legal standing), so for most people it stayed pocket-money fun, not a path to wealth.

Betting on Gladiator Games

Gladiator games were staged fights that took place all over Rome but famously at the Colosseum. What is lesser known is how much the gladiator stands buzzed with side bets: friends and strangers wagered coins, drinks, or favors on who would win, how long a bout would last, who would draw first blood, and if the defeated fighter would get mercy. Fans picked favorites by gladiator type, by a fighter’s recent record, and by what they spotted in the pre-fight parade: fresh bandages or a swaggering walk could swing the “odds.”

There were no official bookmakers; bets were peer-to-peer, shouted across benches or pooled among groups with someone keeping tally on a wax tablet. Small “prop” bets were common: number of hits, who falls first, even whether the the show’s sponsor would let the loser of the gladiator bout live. Graffiti and chants backing named fighters show how popular and noisy this gambling culture was: part bragging rights, part pocket money, all spectacle.

Why are people gambling today?

People in Ancient Rome at the peak of the empire clearly had a desire to escape the underclass through speculation rather than labor. But where Rome differs from today is the regulation on speculation amd its scale. In Imperial Rome, not everyone in the public could own shares in the publicani and speculate on grain prices. Gambling and gladiator bets were a minor, social spend; they were heavily regulated and very few cases show lasting fortunes made purely at the dice table.

People have a lot of explanations for why the world is now gambling. Financial nihilism, rising housing prices, a feeling like people can’t escape the underclass with labor, wage growth stagnation, lack of community, cultural rot, among others.

But this sentiment has existed many times over human history, usually at the height of empires: the Roman Empire in the 2nd century AD, the Dutch Republic during the Tulip mania of the 1630s, the British Empire during the South Sea bubble of the 18th Century, and the American empire during the roaring 1920s. In all these periods, there was an underlying sentiment that financial speculation yielded better results than hard work. Yet, it still didn’t result in mass, consumer scale speculation. Less than a thousand people participated in the Tulip mania but hundreds of millions of people are regularly engaging in financial speculation today.

So what is the primary reason? De-regulation. It used to be difficult for businessmen to run gambling businesses and for people to gamble. Now, it’s easy. The Unlawful Internet Gambling Enforcement Act of 2006 cracked down on online gambling, but explicitly carved out fantasy sports as a “game of skill”. PASPA, which banned sports betting in 1992, was overturned by the US Supreme Court in 2018. Thirty eight states now allow sports betting. In 2005, the SEC approved the listing of short dated options, which are effectively gambling instruments for retail traders. Crypto assets would’ve been treated as unregistered securities and been banned in the 20th century, but they are permitted today. State lotteries, which were banned or tightly restricted till the 1970s, are now legalized across nearly every US state.

Part of the reason for the increase in speculation is smartphones, but the main reason is gambling de-regulation, which allows founders to launch and advertise slot machines delivered through mobile apps.

A casino in every town and in the pocket of every individual wasn’t legal or morally acceptable for almost all of human history, including Ancient Rome. Today, it is.

Edward Chancellor, Devil Take the Hindmost: A History of Financial Speculation (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1999), ch. 1.

Geoffrey Rickman, The Corn Supply of Ancient Rome (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980)

In The Ancient Economy, Moses I. Finley writes about Roman senators who benefited from grain speculation. Cicero, a Roman statesman, accused Gaius Verres, a corrupt governor of Sicily, of hoarding grains, manipulating the market, and abusing insider information. He was prosecuted in 70 BC.

Encyclopaedia Romana, “Denarius,” University of Chicago (accessed September 11, 2025)

“A casino in every town and in the pocket of every individual wasn’t legal or morally acceptable for almost all of human history, including Ancient Rome. Today, it is.”

I reckon it’s up for debate if today’s gambling culture is morally acceptable… Thanks for nerd sniping me with Ancient Rome x Contemporary Social Problem crossover.